Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe International Energy Agency thinks peak oil use is in sight this decade as the world switches to renewables. What is driving this shift – and what is still standing in the way?

The idea of “peak oil” – a peak in the amount of oil we can physically extract, followed by an irreversible decline in production – has been around for decades. So far, though, it has never been reached on a global level.

In June, however, the International Energy Agency (IEA) – a global energy organisation that provides governments with analyses and policy support – announced we may soon reach a different but related value: a peak in the global use of (or “demand for”) oil.

“We think that peak will be before the end of the decade, but just after 2028, so 2029 or 2030, most likely,” says Ciarán Healy, an IEA oil market analyst and co-author of the report. “We have this picture of growth, but slowing growth [this decade], and oil staying very significant, but maybe the turning points are in sight.”

But it would still be an important real-world signal that the energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables is taking place on a global scale.

So, what lies behind these numbers – and what is preventing a faster decline? BBC Future here digs into the huge global changes happening behind these predictions.

Fossil-fuelling a fracas

A row has erupted at the COP28 summit in Dubai over earlier comments by its president, the UAE’s Sultan al-Jaber.

“There is no science out there, or no scenario out there, that says that the phase-out of fossil fuel is what’s going to achieve 1.5C,” he told an online meeting on 21 November.

Mr Jaber has hit back at claims the comments show he denies a core aspect of climate science.

Until the early 2010s, discussions over peak oil generally exclusively referred to concerns over peak oil production: the point at which crude oil reaches its maximum production capacity, followed by an irreversible decline.

“There’s always been new discoveries or new technologies, new ways of extracting oil,” says Krista Halttunen, a research fellow in sustainable finance at the University of Oxford who co-authored a paper last year on peak oil while a PhD researcher at Imperial College London. “So we’ve never actually reached a peak – oil production capacity has been growing the entire time that we’ve had oil, really.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs the world has begun to make efforts to move away from fossil fuels, a new concept of peak fossil fuels has emerged: that we will hopefully start cutting our need for them far before we use up all that is possible to extract from the Earth’s crust. This is the point the IEA now thinks the world will reach at the end of the 2020s.

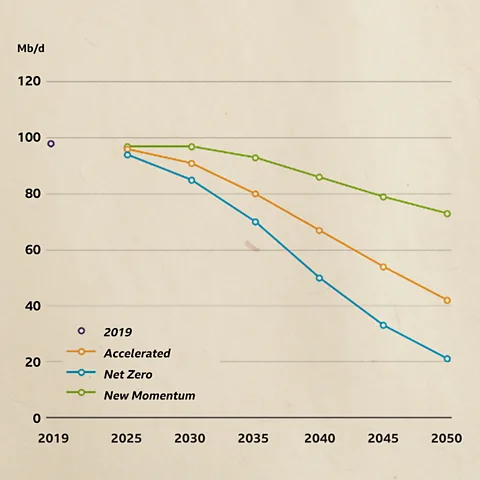

The IEA’s new projections come from its latest medium-term oil report and are broadly aligned with its “stated policies scenario” (Steps) – a relatively conservative global scenario, which is based on what has already been put in place to achieve climate and other energy goals, rather than assuming all stated goals will be met.

“This is a view of what we think is going to happen based on things that people have said they’re going to do or that we’re confident are going to happen,” says Healy. […]. “We’re doing our best job of trying to say what we think is the likely way things will play out.” For oil demand to decline sooner, additional policy measures and behavioural changes would be needed, the IEA notes.

Even tracking the current use of oil is a big job. “There’s a big team of statisticians here that do nothing else, essentially,” says Healy.

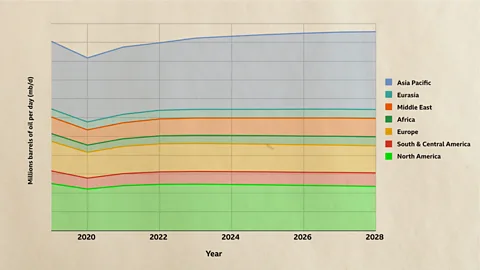

The five-year projection goes up to 2028 – when the IEA thinks the world will be just on the brink of reaching peak oil demand.

The report marks the first time the IEA has found global oil demand will peak in such a short timeframe. “When we ran the model, and there was a peak in it, it was a bit of a surprise,” says Healy. “It was clearly a very interesting result.”

The key to peaking oil use

Of that, around 45% of the total, or around 45 million barrels a day, is used in road fuel for vehicles like cars, trucks and vans, says Healy. It’s here where sweeping changes are already beginning to curb oil demand.

Two big factors are driving this: the advent of alternative vehicle fuels – especially electric vehicles – and increased vehicle efficiency.

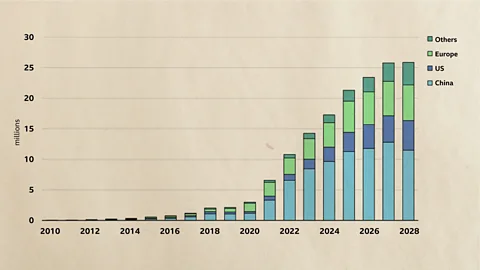

Electric vehicles have been a huge success story, says Healy, and are already having an impact on gasoline demand – especially in China, Europe and North America. Globally, 14% of all new cars sold in 2022 were electric, up from 9% in 2021 and less than 5% in 2020.

“We expect that to continue to have a really big impact, as more and more electric vehicles are sold and displace the use of internal combustion engines in the fleet,” says Healy.

The huge changes afoot in global transport are also not always particularly visible to all, notes Halttunen.

Biofuels

Biofuels – fuels made from organic sources such as crops, trees and organic waste – are also cutting oil demand to some extent.

Gasoline blended with ethanol is now widely used in the US and Australia, while Europe’s E5 and E10 standards mean most petrol and diesel that Europeans buy at the pump contains ethanol.

China, for example, now has around 600,000 electric buses and 13.8 million electric cars on its roads – over half of the world’s electric car fleet.

At the same time, rising vehicle efficiency in many countries across many types of transport, largely driven by government standards, are helping to blunt increases in oil demand.

“As the fleet is replaced, with older cars sold typically 15 to 20 years ago being replaced by new and much more efficient cars, or newer planes replacing much less efficient older planes [… it] helps to really limit the increase in all these different categories,” says Healy.

Of course, these two limiting factors on global oil in transport use are being counteracted to some extent by the rising desire of people all over the globe to move about more.

“As populations grow, as the economy grows, people get richer in various parts of the world, especially in lower-to-middle-income countries,” says Healy.

“You expect there to be this underlying upward pressure on people’s demand for mobility and the implied fuel demand that goes with that.”

The IEA thinks India, for example, will assume the fastest-growing role in the global oil market over the next five years.

Meanwhile, the insatiable rise of energy-hungry SUVs is driving up CO2 emissions, especially in the US.

Still, by 2026, IEA expects overall oil use in transport to peak and begin to decline. The reason overall oil demand will still be rising at this point is largely down to another sector altogether.

The rising production of plastics

Petrochemicals – chemical products derived from petroleum – are used to make all sorts of things from fertilisers and synthetic rubber to plastics and synthetic clothing. They currently account for around 16% of global oil use.

Driven by rising use of plastics and synthetic fibres, the use of petrochemical feedstocks continue to rise right through the IEA’s forecast, outweighing the fall in transport demand right up to the end of the decade.

China is also a big player here: it is investing huge amounts in refineries to substitute current imports of plastics and fibres, locking in growth of the sector.

All this means the IEA doesn’t think last year’s global treaty to tackle plastic waste will have much of an impact on rising plastics production – at least not in the next five years. However, “in five years time, that might be one of the stories we’re really honing in”, says Healy.

The IEA is not alone in its findings about imminent peak oil demand – in fact some oil companies think it may have already happened.

“BP is telling its shareholders that its main product is past its best. It’s downhill from here,” Hannah Ritchie, lead researcher at Our World in Data at the University of Oxford, wrote in an article about BP’s forecast.

BP also says the primary reason behind this declining oil demand are changes in road transport, with the increasing efficiency of cars the main cause this decade, and the switch to electric cars the main driver by 2050.

Even if this begins as a slow declining trend, says Halttunen, “it’s still a huge shift from the way investors have looked at the oil industry before and the companies have looked at their strategy before”.

Reaching peak oil demand, as well as coal and gas, is a necessary step on the way to cutting greenhouse gas emissions – but there will still be a long way to go after that before a major reduction is seen in fossil fuel use.

“The single biggest thing that we have to do to mitigate climate change is to stop burning fossil fuels,” says Halttunen. “We’re so far from actually stopping, but any signs that we can reduce, or at least stop the growth, would be welcome.”

However, a scenario where fossil fuels are simply less valuable – as would occur under a switch to renewables – is probably more realistic than one where fossil fuel companies willingly leave cash in the ground, she adds.

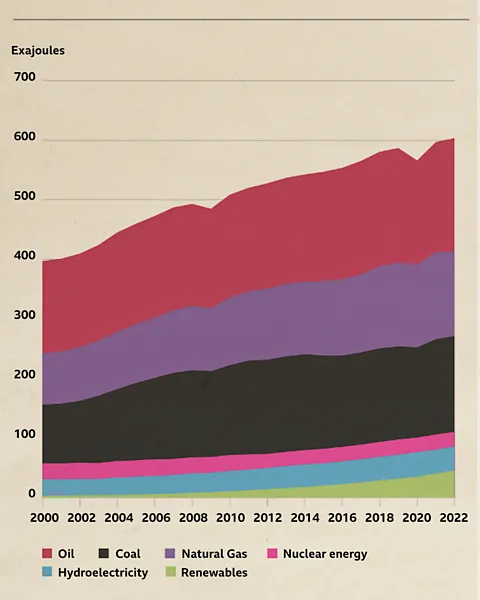

Even to get to these levels has been incredible growth for renewables, says Halttunen – surpassing all the expectations of the International Energy Agency. But global energy use is also rising – the pandemic dip seen in the graph above was only temporary. “We still have developing countries increasing their energy use, even as some developed countries are actually reducing [use],” says Halttunen. If overall energy use outpaces renewables growth, we won’t start reducing fossil fuels.

Healy says he sees the IEA’s peak oil demand projection as “a hopeful thing” which shows there are already visible, real-world consequences to the right climate policies. But he also notes there is still a long way to go when it comes to curbing climate change.

“This isn’t enough, this isn’t close to the net zero trajectory,” he says. “There is an enormous amount more to be done to get us onto that path.”

* This story was originally published in July 2023 and updated on 4 December 2023 during the COP28 talks.