Features correspondent

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittOnce the end point of the main rail line connecting the Great Lakes to the Atlantic, Depot Harbour is now disappearing back into the forest.

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittA black bear scrambled out of the underbrush and lumbered across Old Tracks Road, pausing for a brief moment before disappearing into the thick trees that bordered the muddy, pot-holed track. This road is all that remains of the railway that once lead to Depot Harbour.

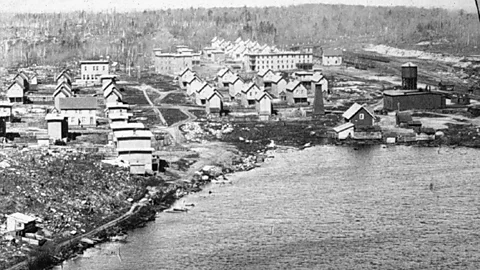

West Parry Sound District Museum’s Dave Thomas Collection

West Parry Sound District Museum’s Dave Thomas CollectionAbout 250km north of Toronto on Ontario’s Georgian Bay, Depot Harbour was once the end point of the main rail line connecting the Great Lakes to the Atlantic. The first train ran on 7 January 1897, and by the 1920s trains were arriving every 20 minutes to pick up timber, wheat, coal and iron ore from ships arriving from Chicago and Milwaukee, and transport them east to Ottawa, Montreal and Portland, Maine.

In the early 20th Century, Depot Harbour was booming, with more than 100 houses, churches, schools, stores, hotels, freight sheds, grain elevators and docks. The population grew with each passing year, forming a melting pot of cultures, including Irish, Italian and Polish. In its heyday, Depot Harbour was home to more than 1,500 permanent residents.

But the settlement’s existence came at a steep cost.

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittThat was our land and we never lost interest in it,” said Chief Warren Tabobondung of the Wasauksing First Nation.

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittA few kilometres north-east of Depot Harbour, the now-charming holiday town of Parry Sound was a thriving lumber town in the 1800s. Its access to the Great Lakes and deep harbour made it the logical place to transfer goods from ship to train.

In 1895, John Rudolphus Booth, a wealthy lumber and railroad baron concerned about the shipment of his own timber, took steps to begin construction of a railroad between Parry Sound and Ottawa. When the owners of Parry Sound’s harbourfront refused to negotiate on the price of their land, Booth re-routed his track to nearby Parry Island – land that at the time was part of the Wasauksing First Nation Parry Island Reserve.

Because property laws at the end of the 19th Century paid little regard to indigenous land rights, the Wasauksing First Nation had little say in the matter. Booth was able to easily take ownership of the area that would soon become the site of Depot Harbour.

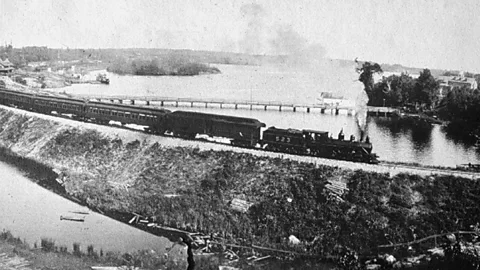

West Parry Sound District Museum’s Dave Thomas Collection

West Parry Sound District Museum’s Dave Thomas CollectionIn the early 20th Century, competition in the railroad industry was fierce. The Canadian Pacific Railway purchased the Parry Sound harbour in 1907 and brought the railroad to Parry Sound as Booth had originally intended. With more goods moving through Parry Sound, Depot Harbour entered into a period of slow decline. Events in the 1930s sealed the town’s fate: when grain prices plummeted during the Great Depression and a damaged rail bridge to the north couldn’t be repaired, residents moved away.

Depot Harbour gained new life during World War II, when a nearby munitions factory used one of the town’s abandoned grain elevators to store excess cordite, a propellant used to make ammunition. But on 14 August 1945, as residents of Parry Sound celebrated the Japanese surrender and the end of the war, a cordite-filled grain elevator in Depot Harbour mysteriously caught fire, lighting the sky for miles around. What was left of the once thriving town went up in flames.

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittToday the harbour sits empty. The crumbling remains of a cement pavement run alongside where the train tracks would have been. Out of the waist-high brush peek the lichen-covered foundations of houses and shops – the forest has swallowed the rest. The only sounds come from bees and mosquitoes humming among the sunset-hued tiger lilies.

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittThe town of Depot Harbour was never rebuilt, but industrial activity didn’t shut down completely. Just after the war, Century Coal Company used the harbour as a coal distribution terminal until demand for coal dropped off in the late 1950s; the National Steel Corporation then took over, using the wharf for loading iron ore onto lake freighters.

Chief Tabobondung remembers the bustling scene of the 1970s: trains carrying iron ore from northern Ontario rumbling past the remains of Depot Harbour to ships waiting just off shore. It was his grandmother, Florence Tabobondung, who helped put an end to industrial activity in the area for good.

“My grandmother was chief for almost three decades,” Chief Tabobondung said, “and anyone my age would certainly remember the day in the mid-‘80s when she led us children down the railroad tracks to protest.”

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittIn 1986, the train left Depot Harbour for the last time.

The tracks have since been torn up and replaced with Old Tracks Road. The old railroad bridge that connects Parry Island to the mainland has been remodelled to allow cars to reach Parry Island and the Wasauksing First Nation community.

Chief Tabobondung remembers playing as a child among the remnants of Depot Harbour. “There are some high rocks near what we call The Church Steps, near the foundation of the old Catholic church, and in the summertime, we would dive off them, he said. “You can still see the steps and the concrete stairway up to the foundation. And we used to pick apples up there – that was one of the highlights of the summer on the Depot lands.”

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittIt’s been more than 100 years since Booth expropriated First Nation land for the creation of the railroad and Depot Harbour. Industrialisation has left a physical scar, and the Wasauksing want the site cleaned up before they take full responsibility for the land; the property is currently being held in a trust on their behalf.

But lingering environmental evaluations haven’t kept the Wasauksing from re-appropriating the land for cultural use. On the first weekend in August, the First Nation holds its annual three-day pow wow on ground where Depot Harbour houses once stood. There’s traditional dancing and food, and everyone is welcome.

“The community wanted to put a stake back into that ground and do something significant there that represented them,” Chief Tabobondung said.

Sarah Hewitt

Sarah HewittThe railroad is gone and the harbour is quiet. What’s left of Depot Harbour is integrated into the Wasauksing First Nation’s history and future. Depot Harbour is at once both a ghost town and a living place.