ViewStock/Alamy

ViewStock/AlamyAeroplanes are incredibly polluting, but could we ever live completely without them?

Aviation has long been a pain in the neck for those working to cut human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. It is the pinnacle of a “hard-to-decarbonise” sector: energy-intensive, lacking in immediate technical options to make it lower carbon, and strongly associated with the lifestyles of the richest and most powerful in society.

Demand management – essentially people flying less – is the most effective way to reduce these emissions this decade, according to a recent report from Transport & Environment, an environmental non-profit organisatoin. Technologies such as sustainable aviation fuels, more efficient planes and electric aircraft will play a bigger role in the 2030s, it said.

But what would happen if people across the world suddenly stopped flying completely? A world of no flights would present some serious logistical challenges, but could also open up the door to huge changes to other, lower-carbon forms of transport. We are unlikely to ever cut out aviation completely, and we likely wouldn’t want to. But posing this hypothetical question opens up the door to what we could be doing far more of to reduce aviation’s heavy impact on the climate.

Grounding all flights on Earth would immediately put a stop to the 2.5% (and growing) of annual CO2 emissions which come from burning fuel in aeroplanes, cutting CO2 emissions by around one billion tonnes per year and eliminating a sector previously leading to rising emissions.

But aviation has other climate impacts too, meaning that the immediate impact on warming of stopping all flights would be far larger than the reduction in CO2 alone. “In addition to CO2, there’s a variety of other effects that planes cause,” says Sally Cairns, a transport policy researcher at the University of Leeds. “The shortest-term effect, and one of the biggest effects, is the formation of contrails, which are the white lines you see in the sky and the associated formation of cirrus clouds.”

ICCT

ICCT“It doesn’t affect many people at all on that basis,” says Stefan Gössling, aviation researcher at Linnaeus University in Sweden. “We had a period with close to zero flights [due to the Covid-19 pandemic], and I think what we learned is that we can do without.”

People with homes in two countries would hastily have to choose which location they wanted to live in, while people who fly frequently for weekend trips and holidays would also face a large change in lifestyle. Holidays would mostly need to be done in places accessible by train, bus, car and ferry, nudging people towards staying in their own or nearby countries.

This could in turn lead to better leisure opportunities for local people in these economies, also providing new jobs, says Cairns. “If you make it an attractive place for people within your country to come and visit, you probably also mean that the local residents have better facilities.”

“As much as there would be problems from stopping air travel tomorrow, I would put that at the top of the list,” says Leo Murray, director of innovation at climate charity Possible. “It’s probably the most important thing. Because there’s a whole bunch of people who would need to find new livelihoods.” Other countries would need to find ways to support these countries, he adds.

The grounding of all planes would also affect the 11 million people around the world who work directly in the aviation industry, such as airport operators, customs and immigration roles, flight attendants, pilots and engineers. A further 18 million people working in businesses supported by aviation indirectly, such as fuel suppliers and call centres, would also face unemployment.

R. Wang/ Alamy

R. Wang/ AlamyAnother difficult challenge would be people who live far away from their loved ones and families. “Probably the most challenging area is visiting family and friends,” says Cairns. “I think that would cause the greatest pain.”

Malithi Fernando, a policy analyst at the International Transport Forum, thinks many people would end up living closer to the people they visit often. Many people would relocate to be closer to their loved ones, requiring more flexible workplaces allowing remote work and more time for travel, she says.

However, you would not see major shortages in supermarkets or clothing stores in a world without planes, says Fernando. “[Bulk goods] are transported using a very different supply chain network, shipping across oceans, and then road or rail or barges and inland waterways. So overall, I think there would be a smaller impact on freight.”

Some air cargo is lifesaving, however. Air freight is used to ship medical supplies and pharmaceuticals around the world. It played a major role in delivering vaccines during the pandemic, for example. It is also used during humanitarian disasters to deliver food, water and medicines. Finding alternatives for delivering time-sensitive medicines or urgent food supplies around the world would not be easy. “With more hurricanes, typhoons, and everything else caused by climate change [this] obviously isn’t going to go away, it might become an increasing issue,” says Cairns.

P. Schatz/Alamy

P. Schatz/AlamyTravelling far in a world without planes

A world where flying was abruptly stopped would create many complications for travel. “‘Suddenly’ is always bad for people because it forces them to make decisions and everything is very disruptive,” says Gössling. “So if you really change things overnight, it’s difficult.”

Aviation has a unique combination of two factors not seen together in any other transport mode, says Fernando. Firstly, it’s fast, both in terms of its speed and its ability to go directly from a to b, easily passing over seas, mountains and lakes. Second, unlike rail and road, it does not require dedicated infrastructure en route between two destinations, so typically requires lower investment up front.

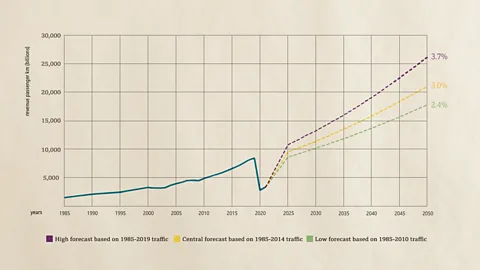

The best alternative to aeroplanes when it comes to speed is high-speed rail – trains with average speeds over around 200km (124 miles) per hour. “It’s the only way we can move a great number of people at high speeds over large distances at a reasonable price,” says Gössling.

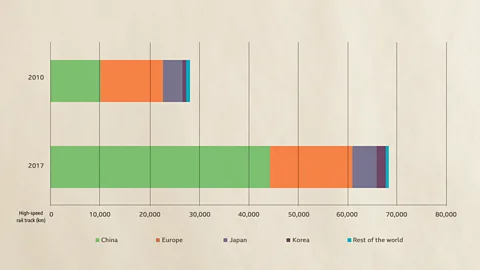

China is the undisputed leader in high-speed rail, with well over half the world’s lines – some 40,000km (25,000 miles)of high-speed rail lines, with plans to raise this to 70,000km (43.000 miles) by 2035. China’s longest route is almost 2,300km (1,400 miles), stretching between Beijing and Guangzhou, a similar distance to that between New York and Miami, or Paris and Tallinn, with a travel time of approximately eight hours.

“[China] has done great work in terms of not just establishing high-speed railways but also in terms of creating some of the best in the world, without vibrations, that are really, really comfortable in terms of taking people at high speeds through the country,” says Gössling.

IEA

IEAA recent analysis from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) found that even today, around 26% of US flights could be replaced by car, bus or high-speed rail. Another 28% of flights could in theory be replaced by high-speed rail, but are between less populated urban centres, meaning not enough people would travel on them make the investment in high-speed rail infrastructure worth it, says Sola Zheng, a researcher at ICCT who did the analysis. In a world of no flying, however, there would likely be more political and taxpayer willingness to build high-speed rail, as well as a higher tolerance for travel time, says Zheng.

Where high-speed networks wouldn’t work due to high upfront costs, lower speed rail would also be a good option, says Fernando. “Regular rail networks might make more sense in a larger variety of situations.” Sleeper trains could make overnight travel of 8-12 hours convenient. There is scope for far more innovation and development on sleeper trains, says Cairns. “The consequence is that the journey becomes part of the holiday.”

The money previously spent on subsidies to airports and airlines could go instead to rolling out this rail network. Huge care would be needed in doing this though, as rail infrastructure can have negative impacts on local people and natural habitats. “There are also of course emissions associated with the infrastructure,” notes Fernando. Most important for rail would be avoiding any new non-electrified rail networks, she adds.

Without planes, long-distance coaches would also become seen as a viable way to travel long distances, especially with a focus on comfort. Fernando notes that buses have one of the two unique factors aviation has: the flexibility of not requiring new en route infrastructure. “You’re likely going to be using roads that are already there. So they are a low-investment option for longer distance travel.”

The expansion of other ways to travel would also provide new jobs for newly unemployed aviation workers, from engineers to flight attendants. “Airlines have always had this kind of cachet as a sort of luxury kind of leisure type activity,” says Cairns. You could imagine a luxury airline running luxury coach tours to Spain with a stopover in a French chateau or gourmet market on the way, for instance, she says.

Driverless cars, once they become available, could also provide a viable alternative to flying, allowing people to sleep or work through long journeys. However, large-scale use of single-occupancy driverless cars – even if they are electric – would be bad news for the climate and congestion, says Fernando. A shared-occupancy model could overcome this issue, she adds.

Of course, there’s one obvious gap where rail and road simply couldn’t help: journeys across seas and oceans. In a world of no flying, the main alternative would be ships: already used to move around the vast majority of the world’s freight.

Travelling from England to New York by ship takes around seven nights; journeys further afield take weeks. Personal journeys of this kind would plummet, with people only willing to undertake them for unique reasons or very infrequently. “I find it a little bit hard to imagine overseas passenger transport becoming hugely popular unless we have some sort of lifestyle changes,” says Fernando.

Of course, ships themselves release plenty of carbon, and a vast increase in passenger travel would be bad news for the climate. Slowing ships down is among the main short-term measures for reducing shipping emissions, Fernando notes: not a great proposition for speedy cross-ocean journeys.

Joe Dunckley/Alamy

Joe Dunckley/AlamyAirships – large, balloon-like vehicles which use gases lighter than air, such as helium or hydrogen, to keep them in the air – are far slower than aeroplanes, but could potentially meet some of the needs currently met via air travel. “I think airships would probably compare favourably with ships,” says Murray. “And probably passengers would prefer airships, because you get seasick on the ocean.” They could be especially useful for passenger transport to island nations, behind deserts, or across mountain ranges, he adds.

However, airships would likely struggle to transport many people quickly across long distances. “It’s hard to see how that could ever be scaled up to become a significant transport,” says Gössling. “To build such huge structures in ways that are really storm proof, for instance, I think that would be very difficult.”

To accommodate the longer times needed to travel by ship and train, employers would need to become more flexible in how they give holidays, or allow people to work on the journey.

There would also be fresh impetus for new creative thinking about how to better connect people together without the need for long-distance travel. More money would pour into technology companies developing better virtual meeting spaces, further accelerating the technology beyond the changes seen in the Covid-19 pandemic. Cairns foresees meetings where all participants are either there physically or represented by a screen, with remote control cameras and directional sound replicating the experience of people actually being at the table with you.

Fully virtual spaces would also flourish. Gössling imagines conferences using scanned 3D avatars of participants which can easily move towards and interact together, allowing them to feel they are really there. The major pediment would probably be people joining from different time zones, he adds.

Meanwhile, empty airports around the world could be repurposed for other activities, such as hosting conferences, meetings or festivals. “Airports tend to be where you get transport links converging. So you’ve got very good connectivity if people wanted to get to those [as] meeting hubs.”

Airports could also be used as local community spaces. “You can also imagine them becoming active travel parks where people can go and try out scooters and hoverboards and bikes and everything else,” says Cairns. Grounded planes themselves could be used for unique hospitality spaces, such as hotels, restaurants and clubs

E. Remsberg/Getty Images

E. Remsberg/Getty ImagesIt’s unlikely we’ll ever wake up to a world without any planes. And we wouldn’t want to: aviation has brought cultures together, prompted new experiences and journeys and provides urgent medicines, humanitarian aid and support for people in need.

“[For] a major reduction in aviation, I think it’s about when not if. I think the climate data is clear on that really,” says Cairns. “If we could get it down to just the hardcore of stuff that we thought was really essential, then actually we could manage that fine. But we have to go from such a different place given where we are at now.”

Fortunately, opportunities do already exist to reduce our dependence on aviation. A focus on our own communities, local tourism and virtual meeting places, as we’ve already seen during the pandemic, could go a long way towards reducing the urge to fly.

In trains, meanwhile, which are far lower carbon than planes, we have a strong alternative to planes. The International Energy Agency has highlighted the shift from aeroplanes and private cars to rail as a key strategy for reaching net zero emissions, and advised governments to set out targeted policies to improve rail.

By 2030, the world needs to cut annual greenhouse gas emissions by around 25 times aviation’s current emissions on top of what governments have already pledged to limit global warming to 1.5C. So eliminating aviation would make a small, but still significant, contribution to closing the gap between our current emissions pathway and where we need to be.

If the aviation industry begins seriously decarbonising planes, we can ultimately hope to move to a world where zero carbon trains and planes are equally as common. For now, though, reducing flights as much as possible remains our best option for limiting the large climate impact of this sector.

Jocelyn Timperley is a freelance climate change reporter and editor. You can find her on Twitter @jloistf.